Publications

Publications on the CLiME site are designed as a digital portal into an educational research resource for issues of structural inequality, urbanism and metropolitan equity. Content is divided between types—articles, reports, presentations and public documents—and by subject. Externally created documents are briefly described, then linked to their sources; original CLiME scholarship is intermixed by subject or can be found under the CLiME tab.

New Jersey homeowners are sinking in monthly bills. In this brief, we explore the sky-high and rapidly rising costs of being a homeowner in New Jersey. This includes both mortgage and non-mortgage housing costs. New Jersey has the property taxes, and among the most expensive housing prices in the country. In addition, New Jersey homeowners pay 20 percent more in utility costs than the national average, and are now facing soaring electricity bills related to supply challenges and the new demands of AI data centers. New Jersey’s homeowners’ insurance premiums are also going up much faster than other states, related to private companies’ responses to more extreme weather and construction and labor costs. As these various costs add up, more homeowners – especially those with lower incomes – are sinking into debt and many are deferring home repairs and maintenance.

In New Jersey, new construction is exempt from price controls for 30 years, even in municipalities with rent control ordinances. Given the other exemptions available to developers, it is questionable whether this exemption is necessary to spur new construction. This memo examines that question by laying out the history of rent control in New Jersey as well as the history of the new construction exemption, looking at case law involving the exemption as well as arguments for the exemption and critique of those arguments, and proposes alternatives to the exemption as either an abolishment or revision of the exemption. The history shows how the moderate nature of rent control in New Jersey suggests that its effect on new construction is overblown, the legislative intent was more about removing barriers to new construction without considering any balance with the prevention of rent gouging, rent control is relevant towards new construction, and significant revision, if not abolishment, of the exemption would have a beneficial effect for existing affordable housing.

The Other Cities: Migration and Gentrification in Jersey City, Newark and Paterson describes housing trends and neighborhood transitions in three mid-sized North Jersey cities that elude conventional descriptions of gentrification. All three have experienced population growth, increased immigration, loss of Black residents and a persistent lack of housing affordability. We describe their particular dynamics three ways: "Bedroom City", "Jobless Gentrification" and "Migrant Metro." Jersey City is the “Bedroom City” where population growth and higher prices are associated with its proximity to jobs across the Hudson River in New York City. Newark is in the midst of “Jobless Gentrification” where investment in expensive market-rate new housing and investor-led renovations raise prices without the corresponding job growth seen in traditional gentrification. Paterson is the “Migrant Metro”, a species of municipalities that have become mosaics of working-class immigration whose density alone—not jobs or new housing—has intensified a lack of affordability. These characteristics distinguish them from traditionally gentrifying cities, but their traits are important bellwethers of urban life across the U.S.

Browse by Topic

In New Jersey, new construction is exempt from price controls for 30 years, even in municipalities with rent control ordinances. Given the other exemptions available to developers, it is questionable whether this exemption is necessary to spur new construction. This memo examines that question by laying out the history of rent control in New Jersey as well as the history of the new construction exemption, looking at case law involving the exemption as well as arguments for the exemption and critique of those arguments, and proposes alternatives to the exemption as either an abolishment or revision of the exemption. The history shows how the moderate nature of rent control in New Jersey suggests that its effect on new construction is overblown, the legislative intent was more about removing barriers to new construction without considering any balance with the prevention of rent gouging, rent control is relevant towards new construction, and significant revision, if not abolishment, of the exemption would have a beneficial effect for existing affordable housing.

The Other Cities: Migration and Gentrification in Jersey City, Newark and Paterson describes housing trends and neighborhood transitions in three mid-sized North Jersey cities that elude conventional descriptions of gentrification. All three have experienced population growth, increased immigration, loss of Black residents and a persistent lack of housing affordability. We describe their particular dynamics three ways: "Bedroom City", "Jobless Gentrification" and "Migrant Metro." Jersey City is the “Bedroom City” where population growth and higher prices are associated with its proximity to jobs across the Hudson River in New York City. Newark is in the midst of “Jobless Gentrification” where investment in expensive market-rate new housing and investor-led renovations raise prices without the corresponding job growth seen in traditional gentrification. Paterson is the “Migrant Metro”, a species of municipalities that have become mosaics of working-class immigration whose density alone—not jobs or new housing—has intensified a lack of affordability. These characteristics distinguish them from traditionally gentrifying cities, but their traits are important bellwethers of urban life across the U.S.

To aid municipalities in regulating anonymous investor buying of 1-4 unit homes we drafted this model ordinance. A companion memorandum analyzes its legality and effectiveness under New Jersey law.

Continuing CLiME’s work on regulating institutional investors of 1-4 unit dwellings in cities like Newark, this legal research memo explains and accompanies model legislation, showing cities exactly how to mandate transparency of ownership among anonymous LLCs.

Few race-conscious public policies displaced African-American individuals and families like the federal urban renewal program from 1949 to 1974. Hundreds of cities spent millions of taxpayer dollars engaging in "slum removal" of entire neighborhoods only recently occupied by Blacks from the Great Migration. Their forced relocation—almost always without statutorily promised relocation expenses and assistance—was a harbinger of the modern ghetto and a blueprint for urban planning approaches that continue to this day.

As part of CLiME's Displacement Project, we began a broad inquiry into urban renewal in 2021. The results will follow in the form of academic papers, policy briefs and here, a growing archive of hard-to-find data on the program's implementation in select U.S. cities. CLiME Fellow and Bloustein graduate Erica Copeland assembled variables on the location, demographic variables and costs associated with primarily African-American displacement for a select period of time. We hope this contributes to a growing body of academic research on an under-appreciated aspect of systemic racism carried out by the federal and local governments at midcentury, whose wealth-retarding effects persist.

Newark housing is too expensive for its residents.

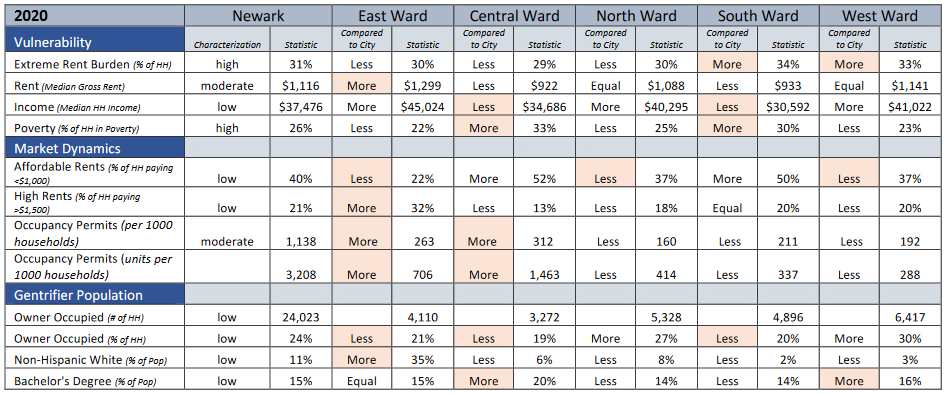

CLiME’s Displacement Risk Indicators Matrix—or DRIM—originated in 2017 as a tool to measure the risk of Newark resident displacement as a result of gentrification. We found then and now that displacement risk continues to be a serious threat to housing stability in Newark as rents rise dramatically among a city of mostly renters. Yet the cause does not appear to be traditional gentrification, because the demographic profile of who lives in the city, their incomes, educations and poverty rates have not changed as dramatically as rents.

The DRIM is divided into three sets of variables set across the city as a whole, the five wards and, for the first time, neighborhoods: vulnerability, market dynamics and “gentrifier population.” Vulnerability variables ask about the economic stresses that households feel. Market dynamics variables ask about rental affordability and new construction. Gentrifier population variables ask whether the city is seeing an influx in the people whose race, housing wealth and educational attainment is associated with gentrifying populations in other cities.

This report shows that the national trend in investor buying of 1-4 unit homes in predominantly Black neighborhoods is most acute in Newark, New Jersey where almost half of all real estate sales were made by institutional buyers. The trend grew out of the foreclosure crisis that wiped out significant middle-class wealth in particular Newark neighborhoods. Those neighborhoods became the targets of investors seeking passive returns from rents. Those largely anonymous outside companies now set neighborhood housing markets on terms that primarily benefit their investors.

While CLiME detected no illegal activity, the threats to Newarkers and government policy goals are significant. They include rapidly rising rents, decreased homeownership, higher barriers to affordable housing production goals, renter displacement and less stable communities. Sadly, this reality continues a long pattern of economic threats to predominantly Black and increasingly Latino neighborhoods in a state whose communities are among the most segregated in the country. From racial exclusion to predatory lending, from foreclosure to the extraction of rents, Newark’s experience demonstrates what can happen when local economies ignore equity.

CLiME’s analysis documents a dramatic increase in institutional investor activity in Newark’s residential market starting around 2013. As of 2020, almost half of all Newark’s residential sales were to institutional buyers.

Housing markets rebounded after the 2007-2009 housing crisis, but homeownership rates never did. Research explains this by the rapid spread of investor buyers into housing markets following the foreclosure crisis. Large investors bought significant numbers of properties that were foreclosed on, at very low prices, frequently converting single-family (1-4 units) into rental properties. They often acquire properties in low-income and moderate-income neighborhoods. ¹

Coming out of the foreclosure crisis, these investor buyers created a new industry around large-scale single-family rental, and have been increasingly active in rental markets generally. These limited liability companies (LLCs), or “corporate landlords”, have reshaped the legal landscape of rental ownership, in part because they limit investor liability. ² Research shows they are less likely to take care of the properties, causing them to fall into disrepair or remain vacant. ³ They are also associated with higher rents and higher rates of eviction. ⁴ Meanwhile, several reports document that the largest among them (e.g.; Invitation Homes, Equity Residential) are making enormous profits even as we experience a profound housing affordability and eviction crisis. ⁵

Orange, East Orange, and Irvington are Black working-class suburban communities. While home to just under 20% of Essex’s population, they are home to almost 40% of all Black residents and only 2% of White residents. These communities are also growing fast, with surging Latino and immigrant populations from the Caribbean.

These inner-ring suburbs are challenged by elevated rates of poverty and a growing unaffordability, and they have few resources to address these pressing needs. In 2020, Orange, East Orange, and Irvington residents generated only $30,000-$40,000 in tax basis for essential public services, such as police, education and sanitation. Meanwhile, nearby Summit residents generated almost four and a half times as many resources as any of these communities, and to serve a much smaller population.

CLiME conducted an affordability and gap analysis of Newark's housing stock and found a severe gap in low-rent units. We estimate that the City needs an additional 16,234 units renting for about $750 per month to meet residents' existing needs.

CLiME’s approach to assessing affordability is rooted in the local context. We calculate a Newark Median Affordable Rent (NMAR) of $763 per month. This is $330 less than Newark’s median market rent, and more than $600 less than Fair Market Rent (FMR), created by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. We also develop a methodological innovation to integrate the City’s rental housing subsidies into the affordability analysis. This procedure, the first of its kind as far as we know, provides a much closer picture of affordability in a City where at least 28% of all units are subsidized.

Land banks are government-created institutions whose mission is to return vacant, abandoned and tax-delinquent properties into productive use. Land banks are empowered to acquire land, eliminate back taxes and tax liens attached to a property in order to create a clean title, maintain the land in compliance with local and state ordinances, and convey the property back into active use. As a mechanism for expediting the disposition of city-owned and/or abandoned properties, land banks can be a significant local government tool either for equitable growth or for more conventional economic development.

Based on the previous DRIM analysis and updated 2017 DRIM analysis, three Wards have been analyzed and found to be Displacement-Risk Neighborhoods: The Central Ward, the South Ward, & the East Ward.

To better understand the trend of displacement that has occurred between years 2000, 2015, & 2017, we conduct a baseline study to analyze the specific displacement risk indicators for one Ward: The Central Ward.

With the increased use of public land for the sake of economic development, cities across the U.S. are facing an urban construction boom. Through the 1980s and 1990s, Newark’s construction boom focused on land-use policies, especially the tax abatement strategies for bringing about capital-intensive projects. Simultaneously, Newark’s shift to a more neo-liberal solution led to a decline in public housing and section 8 vouchers.

As Newark experiences unprecedented growth potential, Newarkers express more and more anxiety about the prospects of housing displacement brought on by the processes of gentrification that have transformed urban neighborhoods across the United States.

Based on the previous DRIM analysis and updated 2017 DRIM analysis, three Wards have been analyzed to be considered as Displacement-Risk Neighborhoods.

To better understand the trend of displacement that has occurred between years 2000 and 2017, we conduct a baseline study to analyze the specific displacement risk indicators.

From the perspective of many low-income families, gentrification is the ultimate social injustice; where “wealthy, usually white, newcomers are congratulated for "improving" a neighborhood whose poor, minority residents are displaced by skyrocketing rents and economic change.”

A social injustice promulgated by local government action, gentrification is no longer confined to our big cities and is increasingly impacting smaller cities and towns as municipalities seek to increase their tax base by luring wealthy residents in search of urban amenities and replace low income residents in the process.

Making Newark Work for Newarkers is the full report of the Rutgers University-Newark Project on Equitable Growth in the City of Newark, written by CLiME and incorporating research conducted in conjunction with a university working group whose work began last April. We viewed the goal of equitable growth first in the context of housing issues before expanding to think about the fabric of community life and economic opportunity in the city.

As Newark experiences unprecedented growth potential, Newarkers express more and more anxiety about the prospects of housing displacement brought on by the processes of gentrification that have transformed urban neighborhoods across the United States. Given the recent history of other cities in its metropolitan neighborhood—New York, Hoboken and Jersey City—Newark would seem poised to attract the kind of global capital that has accelerated so much economic development among …

The City of Newark is undergoing rapid transition, with creative political leadership and development cranes dotting its sky. In February 2016, CLiME launched a comprehensive study of housing trends in the City. In May 2016, CLiME led a Rutgers University-Newark anchor initiative that researching laws and policies that might promote more equitable growth in the City as it changes. This Housing Research Brief represents the first installment of our almost year-long work. It provides quantitative snapshots …

The Rutgers University-Newark Project on Equitable Growth was formed as a team of university researchers led by CLiME to provide research and recommendations about spreading the benefits of potential economic growth to all wards and neighborhoods in the City of Newark. Although housing and housing-related issues dominated our work, we viewed the task more broadly and asked: How does a working-class city in the midst of economic interest from a fast- growing metropolitan region harness …

Each year, psychological trauma arising from community and domestic violence, abuse and neglect brings profound psychological, physiological and academic harm to millions of American children, disproportionately poor children of color. This Article represents the first comprehensive legal analysis of the causes of and remedies for a crisis that can have lifelong and epigenetic consequences. Using civil rights and local government law, it argues that children’s reactions to complex trauma represent the natural symptomatology of severe structural inequality—legally …

What would an equitable DC look like? Communities of color have faced decades of systemic racism and discriminatory policies and practices. These actions have barred people of color from certain jobs and neighborhoods and from opportunities to build wealth, leaving a legacy that persists today. If the nation’s capital were free of its stark racial inequities, it could be a more prosperous and competitive city—one where everyone could reach their full potential and build better lives for themselves and their families.

Washington, DC, is one of most racially segregated cities in the United States, stemming from public policies and private actions that once limited where black residents could live, whether they could secure mortgages, and whom they could buy homes from. Today, Wards 4, 5, 7, and 8 on the east have a majority of black residents, and Wards 2, 3, and 6 on the west are majority white. About half of Hispanic residents live in Wards 1 and 4.

Homeownership is one of the most esteemed values in American society. As such, homeownership is heavily promoted and subsidized by both federal and local governments in the form of tax credits, tax deductions, federally subsidized loans, and federal mortgage insurance from the Federal Housing Authority. The rationale for these subsidies is that homeowners make better citizens, which has been substantiated by researchers using measures such as local voting and church attendance.

FROM THE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Equity and access to opportunity are critical underpinnings of TOGETHER North Jersey’s Regional Plan for Sustainable Development. Therefore, the planning process includes the preparation of this assessment of Fair Housing and Equity in the Northern New Jersey region.

As part of the process to develop a Regional Plan for Sustainable Development (RPSD) for the TOGETHER North Jersey planning region, the TNJ Project Team worked with the TOGETHER North Jersey Steering Committee and Standing Committees to conduct a Fair Housing and Equity Assessment (FHEA) for the region, resulting in this report.

The ultimate objective of regional equity activities is to reform those policies and practices that create and sustain social, racial, economic and environmental inequalities among cities, suburbs and rural areas -- and to bridge the gap between marginalized people and places and the region’s structures of social and economic opportunity. In my book Inside Game/Outside Game, I described three domains of work …

Presented November 7, 2014 as part of the Equity and Opportunity Studies Fellowship workshop series, a partnership between CLiME at the Rutgers Law School, and the Graduate School at Rutgers University-Newark

New Jersey homeowners are sinking in monthly bills. In this brief, we explore the sky-high and rapidly rising costs of being a homeowner in New Jersey. This includes both mortgage and non-mortgage housing costs. New Jersey has the property taxes, and among the most expensive housing prices in the country. In addition, New Jersey homeowners pay 20 percent more in utility costs than the national average, and are now facing soaring electricity bills related to supply challenges and the new demands of AI data centers. New Jersey’s homeowners’ insurance premiums are also going up much faster than other states, related to private companies’ responses to more extreme weather and construction and labor costs. As these various costs add up, more homeowners – especially those with lower incomes – are sinking into debt and many are deferring home repairs and maintenance.

In New Jersey, new construction is exempt from price controls for 30 years, even in municipalities with rent control ordinances. Given the other exemptions available to developers, it is questionable whether this exemption is necessary to spur new construction. This memo examines that question by laying out the history of rent control in New Jersey as well as the history of the new construction exemption, looking at case law involving the exemption as well as arguments for the exemption and critique of those arguments, and proposes alternatives to the exemption as either an abolishment or revision of the exemption. The history shows how the moderate nature of rent control in New Jersey suggests that its effect on new construction is overblown, the legislative intent was more about removing barriers to new construction without considering any balance with the prevention of rent gouging, rent control is relevant towards new construction, and significant revision, if not abolishment, of the exemption would have a beneficial effect for existing affordable housing.

The Other Cities: Migration and Gentrification in Jersey City, Newark and Paterson describes housing trends and neighborhood transitions in three mid-sized North Jersey cities that elude conventional descriptions of gentrification. All three have experienced population growth, increased immigration, loss of Black residents and a persistent lack of housing affordability. We describe their particular dynamics three ways: "Bedroom City", "Jobless Gentrification" and "Migrant Metro." Jersey City is the “Bedroom City” where population growth and higher prices are associated with its proximity to jobs across the Hudson River in New York City. Newark is in the midst of “Jobless Gentrification” where investment in expensive market-rate new housing and investor-led renovations raise prices without the corresponding job growth seen in traditional gentrification. Paterson is the “Migrant Metro”, a species of municipalities that have become mosaics of working-class immigration whose density alone—not jobs or new housing—has intensified a lack of affordability. These characteristics distinguish them from traditionally gentrifying cities, but their traits are important bellwethers of urban life across the U.S.

New Jersey's Assembly Bill A4 represents a landmark effort to comply with the Mount Laurel Doctrine and the state's growing affordable housing crisis by reforming how municipalities meet their fair share housing obligations. At the heart of this legislation is a standardized formula that requires each municipality to calculate its present and prospective affordable housing needs, along with other factors like population growth, land, and income capacity. By decentralizing housing planning, A4 shifts responsibility to local governments from the state and gives them a ten-year window to meet their fair share housing obligations.

This report analyzes the compliance challenges public universities face since the issuance of several executive orders that threaten investigation and defunding for a broad range of activities associated with “DEI” and other undefined terms. In Part I, we examine the language of the federal directives in light of universities’ historic obligations and current circumstances. Many institutions have so far chosen some version of either pre-emptive obedience, wait-and-see inaction or offensive defiance. We suggest that institutions will face some combination of four possible courses of action: continue to obey civil rights law, anticipate new standards, manage risks and defend current practices.

Schools’ circumstances are not uniform. Yet all must conform to current legal standards, which are often inconsistent with the new federal policy directives. To clarify, this report sets out the existing state of the law since Students for Fair Admissions, including the scope and limitations of that Supreme Court decision, the continued allowance of race-neutral means to achieve racially diverse learning environments and the applicable tests used by the Court under Title VI. Since many organizations and institutions have already challenged the federal administration in court, we conclude with an analysis of the legal defenses—mostly on First Amendment grounds—that have so far succeeded in securing injunctions against certain banned practices. Part II of this report sets out best practices universities across the United States have used to stay in compliance with civil rights law yet still maintain environments that are diverse, inclusive and consistent with equitable principles.

Urban renewal, a mid-century federal-local redevelopment program that transformed American cities and displaced millions of Black migrants from the South, was a race-conscious government policy responsible for the enduring suppression of Black wealth. Its racial history and character are untold in legal scholarship. This Article argues that the 25-year regime enacted in the Housing Act of 1949 was a response to the Great Migration of Black workers and families to northern, midwestern, and western cities. It was codified to interact with other segregation policies, such as highway construction, restrictive covenants, redlining, and public housing through the colorblind veneer of rational planning principles. Race planning created durable conditions of “racial bargaining,” the discounted value of wealth-producing transactions in segregated Black communities. Since its mid-century enactment, urban renewal federalized a race-conscious segregation policy that eluded civil rights remedies and framed contemporary urban development programs. This Article shows how this framework sustained the racial wealth gap at the core of this country’s continuing struggle with structural inequality.

New Jersey's Assembly Bill A4 represents a landmark effort to comply with the Mount Laurel Doctrine and the state's growing affordable housing crisis by reforming how municipalities meet their fair share housing obligations. At the heart of this legislation is a standardized formula that requires each municipality to calculate its present and prospective affordable housing needs, along with other factors like population growth, land, and income capacity. By decentralizing housing planning, A4 shifts responsibility to local governments from the state and gives them a ten-year window to meet their fair share housing obligations.

Discussions about Vice President Kamala’ Harris’ record as a progressive prosecutor have offered an opportunity to consider what the next president could do to help spur equitable criminal justice reform. While recognizing that policing is largely a local endeavor, it is important to identify how the next president can leverage existing federal programs to contribute to larger criminal justice reform and equity efforts. In this paper we propose that the next administration restructure the Justice Assistance Grants (JAG) and Community-Oriented Policing Services (COPS) grants in order to support community-based criminal justice programs (CCJP) to achieve equitable criminal justice reform. These programs, which emphasize partnerships between law enforcement, prosecutors, and non-law enforcement organizations, aim to reduce crime and recidivism through rehabilitation, mental health services, and social support. The proposal we offer draws inspiration from Vice President Kamala Harris’s "Back on Track" program, which successfully helped first-time nonviolent offenders avoid incarceration through alternative sentencing that focuses on rehabilitation. The paper argues that similar programs, if federally supported, could help contribute to equitable criminal justice reform by fostering trust between law enforcement and communities, reducing police brutality while also preventing crime and recidivism.

To aid municipalities in regulating anonymous investor buying of 1-4 unit homes we drafted this model ordinance. A companion memorandum analyzes its legality and effectiveness under New Jersey law.

Continuing CLiME’s work on regulating institutional investors of 1-4 unit dwellings in cities like Newark, this legal research memo explains and accompanies model legislation, showing cities exactly how to mandate transparency of ownership among anonymous LLCs.

Few race-conscious public policies displaced African-American individuals and families like the federal urban renewal program from 1949 to 1974. Hundreds of cities spent millions of taxpayer dollars engaging in "slum removal" of entire neighborhoods only recently occupied by Blacks from the Great Migration. Their forced relocation—almost always without statutorily promised relocation expenses and assistance—was a harbinger of the modern ghetto and a blueprint for urban planning approaches that continue to this day.

As part of CLiME's Displacement Project, we began a broad inquiry into urban renewal in 2021. The results will follow in the form of academic papers, policy briefs and here, a growing archive of hard-to-find data on the program's implementation in select U.S. cities. CLiME Fellow and Bloustein graduate Erica Copeland assembled variables on the location, demographic variables and costs associated with primarily African-American displacement for a select period of time. We hope this contributes to a growing body of academic research on an under-appreciated aspect of systemic racism carried out by the federal and local governments at midcentury, whose wealth-retarding effects persist.

This report shows that the national trend in investor buying of 1-4 unit homes in predominantly Black neighborhoods is most acute in Newark, New Jersey where almost half of all real estate sales were made by institutional buyers. The trend grew out of the foreclosure crisis that wiped out significant middle-class wealth in particular Newark neighborhoods. Those neighborhoods became the targets of investors seeking passive returns from rents. Those largely anonymous outside companies now set neighborhood housing markets on terms that primarily benefit their investors.

While CLiME detected no illegal activity, the threats to Newarkers and government policy goals are significant. They include rapidly rising rents, decreased homeownership, higher barriers to affordable housing production goals, renter displacement and less stable communities. Sadly, this reality continues a long pattern of economic threats to predominantly Black and increasingly Latino neighborhoods in a state whose communities are among the most segregated in the country. From racial exclusion to predatory lending, from foreclosure to the extraction of rents, Newark’s experience demonstrates what can happen when local economies ignore equity.

CLiME’s analysis documents a dramatic increase in institutional investor activity in Newark’s residential market starting around 2013. As of 2020, almost half of all Newark’s residential sales were to institutional buyers.

Orange, East Orange, and Irvington are Black working-class suburban communities. While home to just under 20% of Essex’s population, they are home to almost 40% of all Black residents and only 2% of White residents. These communities are also growing fast, with surging Latino and immigrant populations from the Caribbean.

These inner-ring suburbs are challenged by elevated rates of poverty and a growing unaffordability, and they have few resources to address these pressing needs. In 2020, Orange, East Orange, and Irvington residents generated only $30,000-$40,000 in tax basis for essential public services, such as police, education and sanitation. Meanwhile, nearby Summit residents generated almost four and a half times as many resources as any of these communities, and to serve a much smaller population.

This is a structural analysis of police brutality, primarily the exercise of lethal force against unarmed persons, following the 2020 summer of racial reckoning when millions braved a virulent pandemic to protest the lack of legal and institutional accountability that predictably follows the police killings of unarmed black people. A consistent lack of accountability is what binds the individual acts to a design structure in which evidence clearly shows that black bodies are subordinated to some other systemic goal. We do not identify that goal, but we do evaluate the structure that produces predictable outcomes. Our aim is to set out much of the reform landscape—the issues, approaches and proposals from law to policy—and to evaluate them on structural grounds.

CLiME conducted an affordability and gap analysis of Newark's housing stock and found a severe gap in low-rent units. We estimate that the City needs an additional 16,234 units renting for about $750 per month to meet residents' existing needs.

CLiME’s approach to assessing affordability is rooted in the local context. We calculate a Newark Median Affordable Rent (NMAR) of $763 per month. This is $330 less than Newark’s median market rent, and more than $600 less than Fair Market Rent (FMR), created by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. We also develop a methodological innovation to integrate the City’s rental housing subsidies into the affordability analysis. This procedure, the first of its kind as far as we know, provides a much closer picture of affordability in a City where at least 28% of all units are subsidized.

Land banks are government-created institutions whose mission is to return vacant, abandoned and tax-delinquent properties into productive use. Land banks are empowered to acquire land, eliminate back taxes and tax liens attached to a property in order to create a clean title, maintain the land in compliance with local and state ordinances, and convey the property back into active use. As a mechanism for expediting the disposition of city-owned and/or abandoned properties, land banks can be a significant local government tool either for equitable growth or for more conventional economic development.

In this first installment of a faculty essay series, CLiME asked Rutgers professors affiliated with the center to provide brief analysis on some of the many institutional crises exacerbated by the Coronavirus pandemic and to offer solutions. Law Professor Rachel Godsil discuses the loss of public revenues to struggling communities and offers a pipeline to millions. Political Scientist Domingo Morel reveals the growing crisis in public pension fund commitments and a possible path to meeting those obligations. Law Professor Laura Cohen takes readers inside juvenile justice to show the increased risk of viral infection incarcerated youth face as well as the steps advocates are taking on their behalf. Director David Troutt looks into the future to interrogate claims that “we are all in this together” and offers an alternative set of policy priorities we would pursue if mutuality really mattered.

The Rutgers Center on Law, Inequality and Metropolitan Equity joins the national push for transformative change to dismantle systemic racism, a call that follows the coronavirus pandemic and recession and the police killings of several African Americans, including George Floyd. But what does systemic racism mean?

The coronavirus pandemic resembles nothing in any of our lifetimes, and its impact will be felt long after it ends. As an economic story, it will mean immediate loss and uncertainty for many households, probably recession, possibly depression. People who can’t afford to hoard or have jobs that can’t be done remotely will be exposed more often, putting everyone in their households at greater risk and subject to an overburdened health care system. These effects will heighten the social determinants of health for populations that already struggle with underlying conditions statistically more than others. And, with predictable cruelty, it will target black, Latino and lower-income families for disparate death and loss. Recent reports from counties that keep data on race show that it has.

What is Universal Basic Income and how can I read more about it? As UBI is featured in more discussions of mobility policies and progressive federalism, CLiME provides an overview.

As a member of a local affordable housing coalition and partner to Mayor Baraka's effort to implement the second right-to-counsel (RTC) ordinance in the country, CLiME led the research design of such a system and the supporting basis for its legality under New Jersey law.

This memorandum was submitted to the City of Newark in early February, with recommendations for implementing a system of free legal services for indigent Newarkers (incomes below 200 percent of the median) facing imminent eviction proceedings in Essex County court.

Making Newark Work for Newarkers is the full report of the Rutgers University-Newark Project on Equitable Growth in the City of Newark, written by CLiME and incorporating research conducted in conjunction with a university working group whose work began last April. We viewed the goal of equitable growth first in the context of housing issues before expanding to think about the fabric of community life and economic opportunity in the city.

On May 5, 2017, the Rutgers Center on Law, Inequality and Metropolitan Equity (CLiME) hosted an interdisciplinary all-day conference on the institutional responsibility of schools in responding to childhood psychological trauma, particularly in low-SES communities where early life trauma exposure is disturbingly ubiquitous. The conference brought together a group of panelists and audience members from diverse fields related to childhood trauma.

This analysis addresses the disparity in prenatal health outcomes between the City of Paterson and Wayne Township in New Jersey. It guides the reader through the experiences of a hypothetical pregnant woman living in Paterson to examine the institutional and non-institutional factors that prevent this pregnant woman, and others like her, from accessing appropriate prenatal care. This paper also discusses the relationship between the inability to access proper prenatal care and the perpetuation …

Each year, psychological trauma arising from community and domestic violence, abuse and neglect brings profound psychological, physiological and academic harm to millions of American children, disproportionately poor children of color. This Article represents the first comprehensive legal analysis of the causes of and remedies for a crisis that can have lifelong and epigenetic consequences. Using civil rights and local government law, it argues that children’s reactions to complex trauma represent the natural symptomatology of severe structural inequality—legally …

County, New Jersey between 2000 and 2015. The number of children living in poverty in Essex County has increased over the past 15 years, and in some places, quite dramatically. Increasing numbers of Essex County’s poor children live in neighborhoods of extreme poverty. There are also preliminary signs that child poverty has spread into formerly no- or low-poverty neighborhoods.

MORRISTOWN, N.J. — When the morning rush begins at Alexander Hamilton Elementary School here, students lugging oversize backpacks and fluorescent-colored lunchboxes emerge from the school buses that roll in, one after another, for 15 minutes. By the time it ends, children from some of this area’s most privileged enclaves, and from some of its poorest, file through the front doors to begin their day together.

The Morris School District was created in 1971, after a state court decision led to the merger of two Northern New Jersey communities — the mostly white suburbs of Morris Township, and the racially mixed urban hub of Morristown — into one school district for the purpose of maintaining racial and economic balance.

What would an equitable DC look like? Communities of color have faced decades of systemic racism and discriminatory policies and practices. These actions have barred people of color from certain jobs and neighborhoods and from opportunities to build wealth, leaving a legacy that persists today. If the nation’s capital were free of its stark racial inequities, it could be a more prosperous and competitive city—one where everyone could reach their full potential and build better lives for themselves and their families.

Washington, DC, is one of most racially segregated cities in the United States, stemming from public policies and private actions that once limited where black residents could live, whether they could secure mortgages, and whom they could buy homes from. Today, Wards 4, 5, 7, and 8 on the east have a majority of black residents, and Wards 2, 3, and 6 on the west are majority white. About half of Hispanic residents live in Wards 1 and 4.

While it is commonly understood that the 7 million foreclosures that occurred between 2004 and 2015 fueled the Great Recession and have held back a robust recovery, the role of adverse public records is just as significant and less recognized. Nearly 35 million consumers had adverse public records between 2004 and 2015 including bankruptcies, civil judgments and federal tax liens.

Combined with the 7 million foreclosures, this means more than one in five Americans with credit records suffered an adverse event during this period. While It is also commonly understood that the Great Recession ended on June 2009, the total number of consumers having their foreclosure or negative public records still on their credit report actually peaked in 2015. This paper examines the lasting impact of these negative records on consumer spending and economic recovery.

Whereas many U.S. cities have experienced a post-recession economic revival, the accompanying run-up in housing costs is threatening to undermine this success by pricing workers out of cities, lengthening commutes, and diminishing livability, the report notes. As a result, local officials are turning to inclusionary zoning (IZ) as a way to combat the shortage of housing that is affordable to moderate- and lower-income workers.

IZ policies take a market-based approach to affordable housing development by requiring or incentivizing the creation of below-market-rate units in exchange for approval of a market-rate project. Inclusionary zoning leverages private development to achieve a public benefit.

Already the majority of children under five years old in the United States are children of color. By the end of this decade, the majority of people under 18 years old will be of color, and by 2044, our nation will be majority people of color. This growing diversity is an asset, but only if everyone is able to access the opportunities they need to thrive. Poverty is a tremendous barrier to economic and social inclusion and new data added to the National Equity Atlas highlights the vast and persistent racial inequities in who experiences poverty in America.

On June 28, we added a poverty indicator to the Atlas, including breakdowns at three thresholds: 100 percent, 150 percent, and 200 percent of the federal poverty line. We also added an age breakdown to the new poverty indicator, in response to user requests for child poverty data, which allows you to look at poverty rates across different age groups including the population under 5 and 18 years old as well as those 18 to 24, 25 to 64, and 65 and over.

For poor Americans, the place they call home can be a matter of life or death.

The poor in some cities — big ones like New York and Los Angeles, and also quite a few smaller ones like Birmingham, Ala. — live nearly as long as their middle-class neighbors or have seen rising life expectancy in the 21st century. But in some other parts of the country, adults with the lowest incomes die on average as young as people in much poorer nations like Rwanda, and their life spans are getting shorter.

In those differences, documented in sweeping new research, lies an optimistic message: The right mix of steps to improve habits and public health could help people live longer, regardless of how much money they make.

"In this post we will explore the degree of income inequality seen in New Jersey’s municipalities. Using the same process as in our previous analysis where we explored the Gini Index and 80/20 Household Income Ratio of US counties, here we can get a more granular view of inequality seen within our counties.

Using the interactive map and table feature below, we can see the Gini Index, the 80/20 Household Income Ratio, and the income limits for the 20% and 80% cutpoints for every New Jersey municipality. This information, along with margins of error are displayed when hovering over or clicking a municipality on the maps. Options for filtering the maps and table are found on the right-hand side of the feature."

"Flint is one of the extreme examples of how our country has allowed geographic divisions by race and income to result in reverse–Robin Hood exploitation of those with the least power.

We’ve used free trade agreements, race-to-the-bottom economic development poaching, and inconsistent union rules to allow corporations to make a fortune off of cities like Flint and then pack up and leave for cheaper workers.

New Jersey homeowners are sinking in monthly bills. In this brief, we explore the sky-high and rapidly rising costs of being a homeowner in New Jersey. This includes both mortgage and non-mortgage housing costs. New Jersey has the property taxes, and among the most expensive housing prices in the country. In addition, New Jersey homeowners pay 20 percent more in utility costs than the national average, and are now facing soaring electricity bills related to supply challenges and the new demands of AI data centers. New Jersey’s homeowners’ insurance premiums are also going up much faster than other states, related to private companies’ responses to more extreme weather and construction and labor costs. As these various costs add up, more homeowners – especially those with lower incomes – are sinking into debt and many are deferring home repairs and maintenance.

This report shows that the national trend in investor buying of 1-4 unit homes in predominantly Black neighborhoods is most acute in Newark, New Jersey where almost half of all real estate sales were made by institutional buyers. The trend grew out of the foreclosure crisis that wiped out significant middle-class wealth in particular Newark neighborhoods. Those neighborhoods became the targets of investors seeking passive returns from rents. Those largely anonymous outside companies now set neighborhood housing markets on terms that primarily benefit their investors.

While CLiME detected no illegal activity, the threats to Newarkers and government policy goals are significant. They include rapidly rising rents, decreased homeownership, higher barriers to affordable housing production goals, renter displacement and less stable communities. Sadly, this reality continues a long pattern of economic threats to predominantly Black and increasingly Latino neighborhoods in a state whose communities are among the most segregated in the country. From racial exclusion to predatory lending, from foreclosure to the extraction of rents, Newark’s experience demonstrates what can happen when local economies ignore equity.

CLiME’s analysis documents a dramatic increase in institutional investor activity in Newark’s residential market starting around 2013. As of 2020, almost half of all Newark’s residential sales were to institutional buyers.

CLiME conducted an affordability and gap analysis of Newark's housing stock and found a severe gap in low-rent units. We estimate that the City needs an additional 16,234 units renting for about $750 per month to meet residents' existing needs.

CLiME’s approach to assessing affordability is rooted in the local context. We calculate a Newark Median Affordable Rent (NMAR) of $763 per month. This is $330 less than Newark’s median market rent, and more than $600 less than Fair Market Rent (FMR), created by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. We also develop a methodological innovation to integrate the City’s rental housing subsidies into the affordability analysis. This procedure, the first of its kind as far as we know, provides a much closer picture of affordability in a City where at least 28% of all units are subsidized.

Based on the previous DRIM analysis and updated 2017 DRIM analysis, three Wards have been analyzed and found to be Displacement-Risk Neighborhoods: The Central Ward, the South Ward, & the East Ward.

To better understand the trend of displacement that has occurred between years 2000, 2015, & 2017, we conduct a baseline study to analyze the specific displacement risk indicators for one Ward: The Central Ward.

With the increased use of public land for the sake of economic development, cities across the U.S. are facing an urban construction boom. Through the 1980s and 1990s, Newark’s construction boom focused on land-use policies, especially the tax abatement strategies for bringing about capital-intensive projects. Simultaneously, Newark’s shift to a more neo-liberal solution led to a decline in public housing and section 8 vouchers.

As Newark experiences unprecedented growth potential, Newarkers express more and more anxiety about the prospects of housing displacement brought on by the processes of gentrification that have transformed urban neighborhoods across the United States.

Based on the previous DRIM analysis and updated 2017 DRIM analysis, three Wards have been analyzed to be considered as Displacement-Risk Neighborhoods.

To better understand the trend of displacement that has occurred between years 2000 and 2017, we conduct a baseline study to analyze the specific displacement risk indicators.

What is Universal Basic Income and how can I read more about it? As UBI is featured in more discussions of mobility policies and progressive federalism, CLiME provides an overview.

ABSTRACT: Tax increment financing (TIF) has exploded in popularity on the municipal finance landscape as cities compete for scarce public resources to fund economic development. Previous studies evaluate TIF’s efficacy and ability to spark economic growth.

This research expands the evaluation of TIF by questioning the widespread understanding of TIF as a “self-financing” tool through an analysis of its risks and costs to taxpayers. We present a case study of the Hudson Yards redevelopment project in New York City, the country’s largest TIF-type project.

Making Newark Work for Newarkers is the full report of the Rutgers University-Newark Project on Equitable Growth in the City of Newark, written by CLiME and incorporating research conducted in conjunction with a university working group whose work began last April. We viewed the goal of equitable growth first in the context of housing issues before expanding to think about the fabric of community life and economic opportunity in the city.

As Newark experiences unprecedented growth potential, Newarkers express more and more anxiety about the prospects of housing displacement brought on by the processes of gentrification that have transformed urban neighborhoods across the United States. Given the recent history of other cities in its metropolitan neighborhood—New York, Hoboken and Jersey City—Newark would seem poised to attract the kind of global capital that has accelerated so much economic development among …

The Rutgers University-Newark Project on Equitable Growth was formed as a team of university researchers led by CLiME to provide research and recommendations about spreading the benefits of potential economic growth to all wards and neighborhoods in the City of Newark. Although housing and housing-related issues dominated our work, we viewed the task more broadly and asked: How does a working-class city in the midst of economic interest from a fast- growing metropolitan region harness …

On May 5, 2017, the Rutgers Center on Law, Inequality and Metropolitan Equity (CLiME) hosted an interdisciplinary all-day conference on the institutional responsibility of schools in responding to childhood psychological trauma, particularly in low-SES communities where early life trauma exposure is disturbingly ubiquitous. The conference brought together a group of panelists and audience members from diverse fields related to childhood trauma.

Going to court is a stressful and frequently expensive ordeal. Most court appearances result in a monetary retribution, whether to an adversary or the state, and usually come with fine print. Financial obligation to another always comes with strings attached. For those unable to immediately meet their fiduciary duty, penalties can be severe. Inability to pay a fee often results in the tacking on of another fee, for being unable to pay the initial fine. With all these fines being imposed, one may feel as though being poor is a disadvantage in the justice system. The possibility of going to …

This analysis addresses the disparity in prenatal health outcomes between the City of Paterson and Wayne Township in New Jersey. It guides the reader through the experiences of a hypothetical pregnant woman living in Paterson to examine the institutional and non-institutional factors that prevent this pregnant woman, and others like her, from accessing appropriate prenatal care. This paper also discusses the relationship between the inability to access proper prenatal care and the perpetuation …

Each year, psychological trauma arising from community and domestic violence, abuse and neglect brings profound psychological, physiological and academic harm to millions of American children, disproportionately poor children of color. This Article represents the first comprehensive legal analysis of the causes of and remedies for a crisis that can have lifelong and epigenetic consequences. Using civil rights and local government law, it argues that children’s reactions to complex trauma represent the natural symptomatology of severe structural inequality—legally …

County, New Jersey between 2000 and 2015. The number of children living in poverty in Essex County has increased over the past 15 years, and in some places, quite dramatically. Increasing numbers of Essex County’s poor children live in neighborhoods of extreme poverty. There are also preliminary signs that child poverty has spread into formerly no- or low-poverty neighborhoods.

This report provides a critical and comprehensive review of the empirical literature on the sequelae of childhood exposure to potentially traumatic events (PTEs), with special emphasis on low socioeconomic status (SES) populations at disparate risk for exposure to PTEs across the lifespan. First, I will outline the categories and characteristics of childhood PTEs. Second, I will synthesize research on the proximal and distal consequences of childhood PTE exposure. Third, I will identify significant mediators (i.e., how or why PTE-related outcomes occur) …

Cheryl Sharp, MSW, MWT, Karen Johnson, MSW, LCSW, and Pamela Black from the National Council on Behavioral Health present an excellent overview of on Trauma-Sensitive Schools, including the following seven domains:

Domain 1 Student Assessment

Domain 2 Student and Family Involvement

Domain 3 Trauma Sensitive Educated and Responsive District and School Staff

Domain 4 Trauma-Informed, Evidence Based and Emerging Best Practices

Domain 5 Safe and Secure Environments

Domain 6 Community Outreach and Partnership Building

Domain 7 Ongoing Performance Improvement

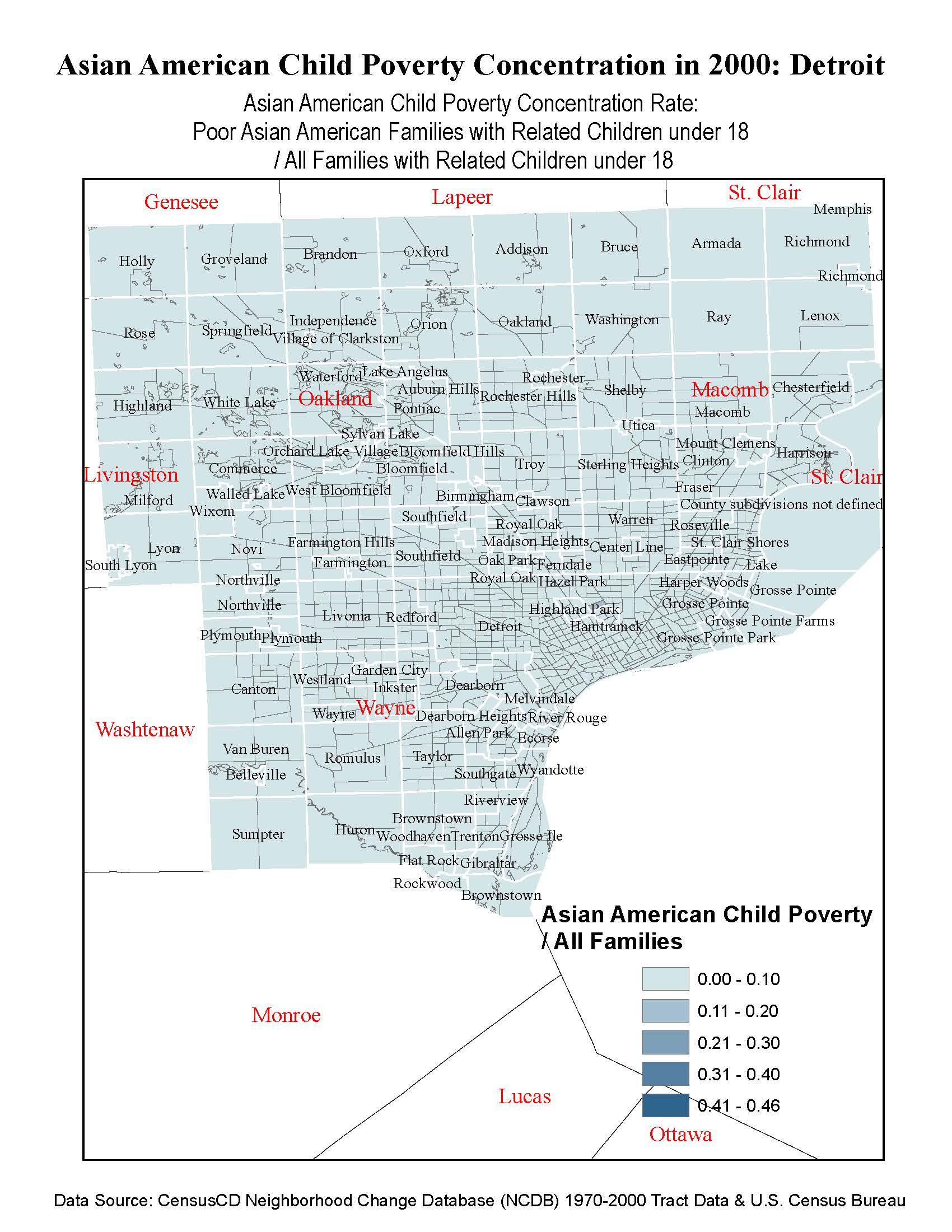

Already the majority of children under five years old in the United States are children of color. By the end of this decade, the majority of people under 18 years old will be of color, and by 2044, our nation will be majority people of color. This growing diversity is an asset, but only if everyone is able to access the opportunities they need to thrive. Poverty is a tremendous barrier to economic and social inclusion and new data added to the National Equity Atlas highlights the vast and persistent racial inequities in who experiences poverty in America.

On June 28, we added a poverty indicator to the Atlas, including breakdowns at three thresholds: 100 percent, 150 percent, and 200 percent of the federal poverty line. We also added an age breakdown to the new poverty indicator, in response to user requests for child poverty data, which allows you to look at poverty rates across different age groups including the population under 5 and 18 years old as well as those 18 to 24, 25 to 64, and 65 and over.

There are as many ways to think about what poverty is as there are to chronicle its historical roots. For many of the 47 million Americans currently living with incomes below the federal poverty line, being poor is working poverty—they manage low-wage, often contingent work, or see their incomes fall temporarily below the official line while struggling through a career transition, a divorce or a serious illness. For every poor person or family, poverty represents a deprivation of key resources that is accompanied by a loss of power over how to reclaim them. For persistently poor …

For poor Americans, the place they call home can be a matter of life or death.

The poor in some cities — big ones like New York and Los Angeles, and also quite a few smaller ones like Birmingham, Ala. — live nearly as long as their middle-class neighbors or have seen rising life expectancy in the 21st century. But in some other parts of the country, adults with the lowest incomes die on average as young as people in much poorer nations like Rwanda, and their life spans are getting shorter.

In those differences, documented in sweeping new research, lies an optimistic message: The right mix of steps to improve habits and public health could help people live longer, regardless of how much money they make.

The Great Recession may have ended in 2009, but despite the subsequent jobs rebound and declining unemployment rate, the number of people living below the federal poverty line in the United States remains stuck at recession-era record levels.

The rapid growth of the nation’s poor population during the 2000s also coincided with significant shifts in the geography of American poverty. Poverty spread beyond its historic urban and rural locales, rising rapidly in smaller metropolitan areas and making the nation’s suburbs home to the largest and fastest-growing poor population in the country. Yet, even as poverty spread to touch more people and places, it became more concentrated in distressed and disadvantaged areas.

INTRO: To write an ethnography about poor urban people is to risk courting controversy. While all ethnographers face questions about how well they knew their site or how much their stories can be trusted, the tone and content of those questions typically remain within the bounds of collegial discourse. Ethnographers of poor minorities have incited distinct passion and at times acrimony, inspiring accusations of stereotyping, misrepresentation, sensationalism, and even cashing in on the problems of the poor (Fischer 2014; see Boelen 1992; Reed 1994; Wacquant 2002; Jones 2010; Betts 2014; Rios 2015).

"According to the latest United Way of Northern New Jersey ALICE Report, 1.2 million households in New Jersey are unable to afford the state’s high cost of living. That number includes those living in poverty and the population called ALICE, which stands for Asset Limited, Income Constrained,Employed.

The ALICE study provides county-by-county and town-level data; cost of living calculations for six family size variations; analysis of how many households are living paycheck to paycheck; and the implications for New Jersey’s future economic stability."

Over the past year, scenes of civil unrest have played out in the deteriorating inner-ring suburb of Ferguson and the traditional urban ghetto of inner-city Baltimore. The proximate cause of these conflicts has been brutal interactions between police and unarmed black men, leading to protests that include violent confrontations with police, but no single incident can explain the full extent of the protesters’ rage and frustration. The riots and protests—which have occurred in racially-segregated, high-poverty neighborhoods, bringing back images of the “long, hot summers” of the 1960s—have sparked a national conversation about race, violence, and policing that is long overdue.

Out of the 12 million single-parent families in the United States, the vast majority—more than 80 percent—are headed by women. These households are more likely than any other demographic group to fall below the poverty line. In fact, census data shows that roughly 40 percent of single-mother-headed families are poor.

Why? Experts point to weak social-safety nets, inadequate child support, and low levels of education, among other factors.

ABSTRACT: We characterize the effects of neighborhoods on children’s earnings and other outcomes in adulthood by studying more than five million families who move across counties in the U.S. Our analysis consists of two parts. In the first part, we present quasi-experimental evidence that neighborhoods affect intergenerational mobility through childhood exposure effects. In particular, the outcomes of children whose families move to a better neighborhood – as measured by the outcomes of children already living there – improve linearly in proportion to the time they spend growing up in that area. We distinguish the causal effects of neighborhoods from confounding factors by comparing the outcomes of siblings within families, studying moves triggered by displacement shocks, and exploiting sharp variation in predicted place effects across birth cohorts, genders, and quantiles.

ABSTRACT: The Moving to Opportunity (MTO) experiment offered randomly selected families living in high poverty housing projects housing vouchers to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods. We present new evidence on the impacts of MTO on children’s long-term outcomes using administrative data from tax returns.

We find that moving to a lower-poverty neighborhood significantly improves college attendance rates and earnings for children who were young (below age 13) when their families moved. These children also live in better neighborhoods themselves as adults and are less likely to become single parents.

Location matters – enormously. If you’re poor and live in the New York area, it’s better to be in Putnam County than in Manhattan or the Bronx. Not only that, the younger you are when you move to Putnam, the better you will do on average. Children who move at earlier ages are less likely to become single parents, more likely to go to college and more likely to earn more.

Every year a poor child spends in Putnam County adds about $150 tohis or her annual household income at age 26, compared with a childhood spent in the average American county. Over the course of a full childhood, which is up to age 20 for the purposes of this analysis, the difference adds up to about $3,100, or 12 percent, more in average income as a young adult.

The Other Cities: Migration and Gentrification in Jersey City, Newark and Paterson describes housing trends and neighborhood transitions in three mid-sized North Jersey cities that elude conventional descriptions of gentrification. All three have experienced population growth, increased immigration, loss of Black residents and a persistent lack of housing affordability. We describe their particular dynamics three ways: "Bedroom City", "Jobless Gentrification" and "Migrant Metro." Jersey City is the “Bedroom City” where population growth and higher prices are associated with its proximity to jobs across the Hudson River in New York City. Newark is in the midst of “Jobless Gentrification” where investment in expensive market-rate new housing and investor-led renovations raise prices without the corresponding job growth seen in traditional gentrification. Paterson is the “Migrant Metro”, a species of municipalities that have become mosaics of working-class immigration whose density alone—not jobs or new housing—has intensified a lack of affordability. These characteristics distinguish them from traditionally gentrifying cities, but their traits are important bellwethers of urban life across the U.S.

This report analyzes the compliance challenges public universities face since the issuance of several executive orders that threaten investigation and defunding for a broad range of activities associated with “DEI” and other undefined terms. In Part I, we examine the language of the federal directives in light of universities’ historic obligations and current circumstances. Many institutions have so far chosen some version of either pre-emptive obedience, wait-and-see inaction or offensive defiance. We suggest that institutions will face some combination of four possible courses of action: continue to obey civil rights law, anticipate new standards, manage risks and defend current practices.

Schools’ circumstances are not uniform. Yet all must conform to current legal standards, which are often inconsistent with the new federal policy directives. To clarify, this report sets out the existing state of the law since Students for Fair Admissions, including the scope and limitations of that Supreme Court decision, the continued allowance of race-neutral means to achieve racially diverse learning environments and the applicable tests used by the Court under Title VI. Since many organizations and institutions have already challenged the federal administration in court, we conclude with an analysis of the legal defenses—mostly on First Amendment grounds—that have so far succeeded in securing injunctions against certain banned practices. Part II of this report sets out best practices universities across the United States have used to stay in compliance with civil rights law yet still maintain environments that are diverse, inclusive and consistent with equitable principles.

Discussions about Vice President Kamala’ Harris’ record as a progressive prosecutor have offered an opportunity to consider what the next president could do to help spur equitable criminal justice reform. While recognizing that policing is largely a local endeavor, it is important to identify how the next president can leverage existing federal programs to contribute to larger criminal justice reform and equity efforts. In this paper we propose that the next administration restructure the Justice Assistance Grants (JAG) and Community-Oriented Policing Services (COPS) grants in order to support community-based criminal justice programs (CCJP) to achieve equitable criminal justice reform. These programs, which emphasize partnerships between law enforcement, prosecutors, and non-law enforcement organizations, aim to reduce crime and recidivism through rehabilitation, mental health services, and social support. The proposal we offer draws inspiration from Vice President Kamala Harris’s "Back on Track" program, which successfully helped first-time nonviolent offenders avoid incarceration through alternative sentencing that focuses on rehabilitation. The paper argues that similar programs, if federally supported, could help contribute to equitable criminal justice reform by fostering trust between law enforcement and communities, reducing police brutality while also preventing crime and recidivism.

This report shows that the national trend in investor buying of 1-4 unit homes in predominantly Black neighborhoods is most acute in Newark, New Jersey where almost half of all real estate sales were made by institutional buyers. The trend grew out of the foreclosure crisis that wiped out significant middle-class wealth in particular Newark neighborhoods. Those neighborhoods became the targets of investors seeking passive returns from rents. Those largely anonymous outside companies now set neighborhood housing markets on terms that primarily benefit their investors.

While CLiME detected no illegal activity, the threats to Newarkers and government policy goals are significant. They include rapidly rising rents, decreased homeownership, higher barriers to affordable housing production goals, renter displacement and less stable communities. Sadly, this reality continues a long pattern of economic threats to predominantly Black and increasingly Latino neighborhoods in a state whose communities are among the most segregated in the country. From racial exclusion to predatory lending, from foreclosure to the extraction of rents, Newark’s experience demonstrates what can happen when local economies ignore equity.

CLiME’s analysis documents a dramatic increase in institutional investor activity in Newark’s residential market starting around 2013. As of 2020, almost half of all Newark’s residential sales were to institutional buyers.

This is a structural analysis of police brutality, primarily the exercise of lethal force against unarmed persons, following the 2020 summer of racial reckoning when millions braved a virulent pandemic to protest the lack of legal and institutional accountability that predictably follows the police killings of unarmed black people. A consistent lack of accountability is what binds the individual acts to a design structure in which evidence clearly shows that black bodies are subordinated to some other systemic goal. We do not identify that goal, but we do evaluate the structure that produces predictable outcomes. Our aim is to set out much of the reform landscape—the issues, approaches and proposals from law to policy—and to evaluate them on structural grounds.

CLiME conducted an affordability and gap analysis of Newark's housing stock and found a severe gap in low-rent units. We estimate that the City needs an additional 16,234 units renting for about $750 per month to meet residents' existing needs.

CLiME’s approach to assessing affordability is rooted in the local context. We calculate a Newark Median Affordable Rent (NMAR) of $763 per month. This is $330 less than Newark’s median market rent, and more than $600 less than Fair Market Rent (FMR), created by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. We also develop a methodological innovation to integrate the City’s rental housing subsidies into the affordability analysis. This procedure, the first of its kind as far as we know, provides a much closer picture of affordability in a City where at least 28% of all units are subsidized.

In this first installment of a faculty essay series, CLiME asked Rutgers professors affiliated with the center to provide brief analysis on some of the many institutional crises exacerbated by the Coronavirus pandemic and to offer solutions. Law Professor Rachel Godsil discuses the loss of public revenues to struggling communities and offers a pipeline to millions. Political Scientist Domingo Morel reveals the growing crisis in public pension fund commitments and a possible path to meeting those obligations. Law Professor Laura Cohen takes readers inside juvenile justice to show the increased risk of viral infection incarcerated youth face as well as the steps advocates are taking on their behalf. Director David Troutt looks into the future to interrogate claims that “we are all in this together” and offers an alternative set of policy priorities we would pursue if mutuality really mattered.

On May 5, 2017, the Rutgers Center on Law, Inequality and Metropolitan Equity (CLiME) hosted an interdisciplinary all-day conference on the institutional responsibility of schools in responding to childhood psychological trauma, particularly in low-SES communities where early life trauma exposure is disturbingly ubiquitous. The conference brought together a group of panelists and audience members from diverse fields related to childhood trauma.

This analysis addresses the disparity in prenatal health outcomes between the City of Paterson and Wayne Township in New Jersey. It guides the reader through the experiences of a hypothetical pregnant woman living in Paterson to examine the institutional and non-institutional factors that prevent this pregnant woman, and others like her, from accessing appropriate prenatal care. This paper also discusses the relationship between the inability to access proper prenatal care and the perpetuation …

Each year, psychological trauma arising from community and domestic violence, abuse and neglect brings profound psychological, physiological and academic harm to millions of American children, disproportionately poor children of color. This Article represents the first comprehensive legal analysis of the causes of and remedies for a crisis that can have lifelong and epigenetic consequences. Using civil rights and local government law, it argues that children’s reactions to complex trauma represent the natural symptomatology of severe structural inequality—legally …

MORRISTOWN, N.J. — When the morning rush begins at Alexander Hamilton Elementary School here, students lugging oversize backpacks and fluorescent-colored lunchboxes emerge from the school buses that roll in, one after another, for 15 minutes. By the time it ends, children from some of this area’s most privileged enclaves, and from some of its poorest, file through the front doors to begin their day together.

The Morris School District was created in 1971, after a state court decision led to the merger of two Northern New Jersey communities — the mostly white suburbs of Morris Township, and the racially mixed urban hub of Morristown — into one school district for the purpose of maintaining racial and economic balance.

Already the majority of children under five years old in the United States are children of color. By the end of this decade, the majority of people under 18 years old will be of color, and by 2044, our nation will be majority people of color. This growing diversity is an asset, but only if everyone is able to access the opportunities they need to thrive. Poverty is a tremendous barrier to economic and social inclusion and new data added to the National Equity Atlas highlights the vast and persistent racial inequities in who experiences poverty in America.

On June 28, we added a poverty indicator to the Atlas, including breakdowns at three thresholds: 100 percent, 150 percent, and 200 percent of the federal poverty line. We also added an age breakdown to the new poverty indicator, in response to user requests for child poverty data, which allows you to look at poverty rates across different age groups including the population under 5 and 18 years old as well as those 18 to 24, 25 to 64, and 65 and over.

The Great Recession may have ended in 2009, but despite the subsequent jobs rebound and declining unemployment rate, the number of people living below the federal poverty line in the United States remains stuck at recession-era record levels.

The rapid growth of the nation’s poor population during the 2000s also coincided with significant shifts in the geography of American poverty. Poverty spread beyond its historic urban and rural locales, rising rapidly in smaller metropolitan areas and making the nation’s suburbs home to the largest and fastest-growing poor population in the country. Yet, even as poverty spread to touch more people and places, it became more concentrated in distressed and disadvantaged areas.

"Flint is one of the extreme examples of how our country has allowed geographic divisions by race and income to result in reverse–Robin Hood exploitation of those with the least power.

We’ve used free trade agreements, race-to-the-bottom economic development poaching, and inconsistent union rules to allow corporations to make a fortune off of cities like Flint and then pack up and leave for cheaper workers.

INTRO: To write an ethnography about poor urban people is to risk courting controversy. While all ethnographers face questions about how well they knew their site or how much their stories can be trusted, the tone and content of those questions typically remain within the bounds of collegial discourse. Ethnographers of poor minorities have incited distinct passion and at times acrimony, inspiring accusations of stereotyping, misrepresentation, sensationalism, and even cashing in on the problems of the poor (Fischer 2014; see Boelen 1992; Reed 1994; Wacquant 2002; Jones 2010; Betts 2014; Rios 2015).

The achievement gap is often defined as the difference in academic achievement of minority and/or low-income students and their White and/or more affluent peers. Its status is evaluated through state standardized assessments, mandated under the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), as well as the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP).